Solitude, Isolation, and the Need for Community

An examination on Mary Shelley’s use of isolation and community to show the ultimate importance of social interaction.

To be human is to be in community. While some periods of solitude can be refreshing and recharging for human’s souls, long term isolation eats away at the very essence of being human. For many, being completely alone is unnatural, uncomfortable. For others, time spent alone is life-giving and necessary. Mary Shelley, in her classic gothic novel, Frankenstein, explores the powerful grip of aloneness. In all of the tragedy and action of the novel, quiet aloneness permeates and ties the novel together. However, not all time alone is the same. Shelley draws a distinct difference between solitude and isolation. Solitude is often a choice–a short sabbatical from life’s miseries. In this way, solitude is gentle and healing. Isolation, on the other hand, is a dangerous, prolonged plight–either self inflicted or forced solitude that leads to obsessive and destructive ends. Shelley’s two protagonists–Victor Frankenstien and his creation, the Monster–embody aloneness throughout the novel, living in solitude or isolation and separate from others and community, although both characters interact with isolation and community vastly differently. Thus, in Frankenstein, Shelley contrasts peaceful solitude with destructive isolation to ultimately argue the essential importance of community for giving life a meaningful purpose.

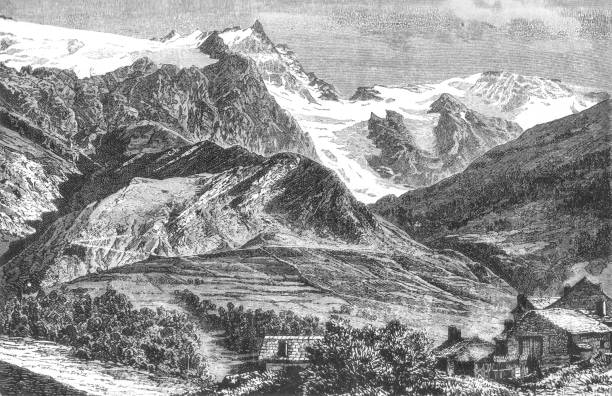

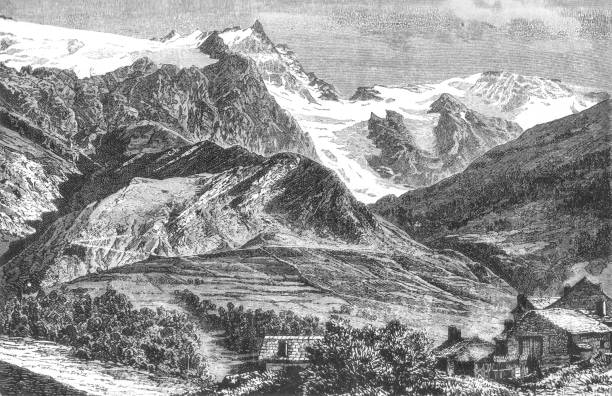

Throughout Frankenstein, characters find restoration in solitude. When Victor and the Monster are alone, experiencing bucolic solitude in nature, their emotional distress subsides and they feel at peace. Indeed, solitude in nature may be the only place Victor mutes his guilty conscience and raw emotions. Throughout the story, Victor struggles with the reality he created, bringing a new “unnatural” life into the world, and his guilt increases further as his creation murders his family. Victor feels the pain of failing to live up to the expectations his creation has of its creator. Victor repeatedly ends up in deep mental and physical health distress requiring months of rehabilitation. However, in all of Frankenstein’s mental anguish, he finds solace in the solitude. Victor, standing alone in nature, says, “these sublime and magnificent scenes afforded me the greatest consolation that I was capable of receiving. They elevated me from all littleness of feeling; and although they did not remove my grief, they subdued and tranquilized it” (Shelley 69). Surrounded by beauty, Frankenstein allows himself solitary peace from the guilt of his murders by proxy to “elevate” himself from the “littleness” of human emotion. In this way, even Victor defines the natural world as better or more valuable than the human-developed world. Additionally, Victor uses almost controlling, forceful diction like “subdue” and “tranquilize” to illustrate the drug-like power solitude in nature holds him in. “Subdue” and “tranquilize” seem to imply a strong and powerful pressure of peace. Victor is not simply alone in nature but he is gripped there by the strength of the scenery. The enormity of the Alp mountain landscape and his natural surroundings when alone in them, help Victor feel small and thus mute the horror he feels for what he has done. After the death of both Justine and William (both murders he feels responsible for) Frankenstein claims, “I was now free… and passed many hours upon the water…often, I say, I was tempted to plunge into the silent lake, that the waters might close over me and my calamities for ever” (Shelley 66). In this section, Victor draws attention to the “silence” and quietness of the lake emphasizing his mode of solitude. Tormented by guilt and unrest, Victor finds rest in his moments alone, pressed by the fantastical powers of nature. Throughout the novel, Victor doesn’t find rest alongside another soul, but only when he is completely alone in his solitude.

In a similar fashion, for the Monster, moments of restorative solitude fuel his benevolence and love for the world. The Monster suffers from rejection of man, society, even his creator. The entire social construct of human community rejects the Monster. Through solitude–again, especially solitude in nature–the Monster is able to in part restore his ability to love, while simultaneously abating his hatred toward mankind. The Monster reveling in nature in moments away from the cottage says, “my spirits were elevated by the enchanting appearance of nature; the past was blotted from my memory, the present was tranquil, and the future gilded by bright rays of hope, and anticipations of joy” (Shelley 84). After suffering from rejection by society, the Monster travels out into nature in solitude and is reformed back into “hope” and “joyful anticipations.” The shift into softer, positive diction alludes to the shift that the Monster experiences when he is alone in peaceful solitude away from the negativity he feels when dejected and alone. Like Victor, the Monster also feels the “tranquil” power that a natural solitude holds. Although not shown as strong or oppressive, the Monster also appreciates the tranquil nature of solitude. However, interestingly, unlike Victor who seems to revel in solitude, the Monster detests his loneliness, even though it temporarily soothes his rage.

In specific scenes of beautiful nature, the Monster’s mental oppression is subdued and he is led back toward what seems to be an innate goodness–strictly different from how Victor responds to solitude. These moments of restorative peacefulness for the Monster are times he can forget his creator’s rejection, and his actual isolation allows himself to be enveloped into awe of a glorious, beautiful world in which he desperately wishes to find a place. In this way, the redemptive moments of solitude for the Monster allow him to be filled with positive joyful emotion, contrasting to Victor’s solitude which does not produce joy nor pleasure, but rather only serves to temporarily mute his overwhelming negative emotions. The Monster says, “I felt emotions of gentleness and pleasure, that had long appeared dead, revive within me” (Shelley 103) and earlier watching the seasons change to spring exclaims, “Happy, happy earth! fit habitation for gods, which, so short a time before, was bleak, damp, and unwholesome” (Shelley 84). Here, Shelley employs contrasts between life-affirming diction and death-filled diction to show the Monsters joy toward his own and nature’s seasonal transformation. At the beginning of both sections Shelley uses life-affirming, positive words like “gentleness” and “pleasure” in the first quote and “happy” in the second quote to show his new found joy in nature. But, the second half of the quotes use negative, death-filled images like “dead,” “revive,” “bleak,” “damp,” and “unwholesome” to show the progress of change in himself and the actual seasons themselves. This process of change is through the Monster’s time in solitude alone watching the seasons progress to beautiful and fullness. Although the Monster wishes for community, he is able to experience moments of joyful and fullness in solitude, not merely isolation, as he experiences the breathtaking beauty of life. The Monster quietly observes the goodness of human life and wants to join in. He wants to become a simpler, more joyful creature.

In this way, for both protagonists, Shelley shows the glory and peacefulness of solitude, but Shelley through the Monster and Victor also draws a sharp contrast between solitude and isolation. Although solitude is seen as a positive force for both Victor and his creation, isolation ultimately causes destruction. This destruction can be first seen in Victor’s process of creating the Monster. Shortly after his mother dies, Frankenstien leaves to attend college to study natural sciences, where he becomes obsessed with creating a new rare and reanimating life. Victor claims his “cheeks had grown pale with study, and my person had become emaciated with confinement” (Shelley 36). Victor, after leaving his idyllic childhood town of Geneva, throws himself into his work, an obsession that ultimately leads Victor to isolate himself from all of his previous communities and connections. Victor calls his self-imposed, forceful isolation his “confinement,” illustrating the constricting manner with which isolation holds Frankenstein’s characters. Contrary to solitude’s ability to free Victor from “the littleness of feeling” or its way of broadening Victor’s scope and happiness, isolation forcefully confines as Victor obsesses over his own passions and self. Enamored with his power trip and wishing to play God, Victor intentionally cuts himself off from any support system that could have forestalled his demise–specifically his family. In earlier chapters, Frankenstein speaks highly of his family, of Elizabeth, and of his friends (Cleveral). However, equally as quickly, Victor no longer contacts them nor involves them in his life, effectively further isolating himself. Victor confesses after receiving a letter from his father that he “knew [his] silence disquieted them” (Shelley 36). Victor sympathizes with his family for his lack of affection and attention; however, already deep within his obsession and creation process, Victor seems unconcerned with reconnecting his family until after his creation is complete. This decision toward isolation proves to be a fatal mistake in Victor’s life.

The result of Victor’s self imposed isolation comes the most destructive force–the Monster–who almost supernaturally comes to life and ultimately grows to be the very embodiment of the effects of isolation. Victor’s isolation, ironically, sends him deeper into an ultimate, unparalleled obsession to create a new life. Frankenstein is obsessed to create a life, despite the fact he has chosen to reject all other companionship. Victor works feverishly with “ardour far exceeding moderation” (Shelley 38). Shelly uses the term “ardour” to highlight the intensity of the scientist’s obsession. Rather than a weaker adjective like enjoyment, Shelley uses “ardour” to strengthen the connection between Victor’s obsessive creation and himself–without any reservation or “moderation” like moths to the flame Victor is endlessly consumed by his science. Even Victor himself can see the downward spiraling nature of his isolation (in his self proclaimed work without “moderation”) and how it ultimately ends with his creation of a creature he loathes. All of Frankenstien’s lonely toiling, grave digging, and reanimating ends with both birth (a new life) and also destruction (murder). Thus, isolation and the lack of community ends with the destruction of Victor’s happiness; Victor’s first impulse at his endless work was “breathless horror and disgust” (Shelley 38). This is where isolation has led him: running away in horror from the output of two years of effort, afraid and alone. Shelley uses the word “breathless” suggesting death and terror to allude to the later truth that his creation will ultimately end in Victor’s own “breathless” death and total destruction.

Sadly, the ultimate output of Frankenstien’s work–the Monster–is similarly relegated into isolation that ends in the destruction of all potential goodness within the Monster, as well as the death of many others as collateral damage. The Monster does not learn of his isolation purely from novels and language but also from the direct rejection of communities to which he wished to belong, fueling his dangerous rage. The Monster, born under the Rousseauian belief of the innate goodness of mankind who loves humanity and claims to be “benevolent and good,” is twisted into evil through his forceful isolation (Shelley 73). Immediately after his creation–his infancy, so to speak–the Monster begins to roam around areas surrounding Ingolstadt, his birthplace. The Monster finds only rejection from all of humanity: “the children shrieked, and one woman fainted…some attacked me, until, grievously bruised by stones and many other kinds of missile weapons” (Shelley 77). The Monster, still “young” vis-a-vis his creation date, is already facing the terror of humanity’s unforgiving nature. Times of youth are deeply impactful on an individual’s psyche and personhood and the Monster’s youth is spent getting “shrieked” at and attacked by villagers. This outright terror and horror pushes the Monster back into isolation as he “escape[s] to the open country” (Shelley 77). Unlike wandering or traveling into the “open country” the Monster says he “escapes” into nature implying a hurried hush to safety. The Monster emphasizes the power of his dejection and rejection from society by using strong diction like “escape.” In his formative “youth”, the Monster is immediately facing social, mental, physical isolation from all beings (other than nature) around him.

Through education and knowledge, the Monster learns of his outcast reality by participating in human culture which fuels his feelings of perceived otherness and isolation. Within his time observing the De Laceys, the Monster finds four books and devours them, one of which is Paradise Lost. In this epic poem, Milton writes on the Genesis story, God’s relationship with man, and ultimately the fall from Eden. After establishing a view of God–a newfound awareness of the created and the creator–the Monster reads his creator’s journal (the Monster’s own origin story). The Monster tells Victor, “I sickened as I read. ‘Hateful day when I received life!’ I exclaimed in agony. ‘Cursed creator!’” Disgusted with his own depraved form and visceral loneliness, the creature points his rage towards his own version of a “creator god”–Victor. The Monster continues, “Why did you form a monster so hideous that even you turned from me in disgust? God in pity made man beautiful and alluring, after his own image; but my form is a filthy type of your’s, more horrid from its very resemblance” (Shelley 95). Juxtaposing God’s love for his creation as retold in Paradise Lost with the rejection of the god-figure in his own life (Victor) crushes the Monster. This image of a physical “turning” mirrors the actions of the old man who the Monster first encounters sees him and “he turned…shirked loudly, and, quitting the hut, ran across the fields” (Shelley 76). The Monster, formally pure and full of goodness unaware of the actual rejection from all of society’s relationships, is wrecked when he learns of how the creator in Paradise Lost loves his beautiful creation. Applying this to his own life only ends in an agonizing lament of “cursed creator!” exacerbating the Monster’s feeling of isolation. The Monster not only does not have a relationship with his creator. Patrick Brantlinger in his essay criticism of Frankenstein, “The Reading Monster,” acknowledges how the creature’s education leads to the amplification of the Monster’s perceived sense of otherness and isolation: “The Monster’s acquisition of language and literacy is, in contrast, the narrative of his coming to self-knowledge, through for him self-knowledge and self-alienation are identical” (Brantlinger 455). The Monster’s reading, listening, observing both helps the Monster grow, learn and become educated, but also sinks him into the realization of his own depravity and loneliness. Instead of emancipation, the Monster’s illuminating education rather leads him into “self-alienation” or isolation. Fueled by the impetus of reading Paradise Lost, the Monster begins realizing the full nature of his plight. From here, the Monster begins his quick descent from newly created purity and an innocent wish to belong into an isolation-induced, dangerous murderous rage toward mankind, but especially Victor.

Although the Monster begins to understand the extent of his aloneness, the De Lacey’s rejection of the creature thrust him into a dangerous, angry isolation. Following the repeated attacks from villages, the Monster finds refuge in a hovel next to a cottage and here the Monster becomes attached and wishes to join in community with “the cottagers.” As the Monster watches the De Lacey’s life, he learns that Felix is Agatha’s brother and their father is blind. He learns of the hardship they face when he steals their food. He learns of poverty. The Monster, in the cover of night, assists the cottagers: “I cleared their path from the snow, and performed those offices that I had seen done by Felix… I heard them, on these occasions, utter the words good spirit, wonderful” (Shelley 83). The Monster performs noble duties that would be done in a caring human community. However, the Monster performs these acts alone, hidden in isolation, out of fear for how he would be received if the community knew he was behind the acts. And for a while, it works. After performing these good deeds, the Monster receives his first positive reactions (“good spirit” and “wonderful”). Motivated by this positivity, he ultimately decides to take the risk and reveal himself to the cottagers. Despite all he has done for the cottagers, even his beloved De Laceys shudder away from him in horror: “Agatha fainted; and Safie, unable to attend to her friend, rushed out of the cottage. Felix darted forward, and with supernatural force tore me from his father” (Shelley 99). The reaction to the Monster hasn’t changed: Humanity still runs away, attacks and hates the Monster. Narrating the scene, the creature even uses the word “supernatural” in reference to Felix’s protection of his father to illustrate the extent of the fear and hate the cottagers have upon seeing the Monster’s own “supernaturalness.” Throughout the novel, the Monster is described as possessing supernatural talents and abilities. Indeed, the Monster’s very creation is supernatural and he projects a “supernatural otherness” that humans immediately perceive, further exacerbating the Monster’s feeling of difference and isolation. The Monster comes to the realization that he doesn’t face natural rejection, but rather a supernatural, deep seeded rejection. Additionally, Shelley uses the repeated image of fainting and running away from the Monster to illustrate how his isolated position remains unchanged and hopeless; the De Laceys, just like the villagers from before, cannot and will not accept him. After their cruel rejection, the Monster becomes vengeful and turns away from his innate goodness to evil.

The Monster’s forced isolation thrusts him into a dangerous passion for evil. The Monster, dejected and angry, seems to understand and reluctantly accepts that he is “a blot upon the earth from which all men fled” (Shelley 87). Like his earlier allusions to Satan and demons, the Monster also describes himself as a “blot”–something unnatural, formless, unhuman, and off putting. Using an impersonal word like “blot” shows that the Monster has now turned away from any hope of humanness and accepted his isolated dehumanization. Dejected and alone the Monster finds solace in nature as stated above, however it cannot overcome the depressing, complete isolation he faces. This passion is fueled into anger against Victor and manifests as Monster torments him and ultimately kills those around Frankenstien. In his isolated wanderings in nature, the creature stumbles upon William (who happens to be Victor’s younger brother) and upon the revelation of their connection, the Monster murders the child. Intentionally targeting Victor, the Monster says, “I, too, can create desolation; my enemy is not impregnable; this death will carry despair to him, and a thousand other miseries shall torment and destroy him” (Shelley 105). Throughout all of the Monster’s threat to Victor the creature uses forceful diction like “death,” “despair,” “miseries,” “torment,” and “destroy” to illustrate his dangerousness. The creator blames his creator for his isolation and now consumed by passion for revenge uses forceful language to show his murderous attitude toward Victor. Additionally, the Monster uses “desolation” as a synonym to isolation. Desolation is a solitude that goes beyond pure aloneness but rather desolation is isolation where any place for companionship is filled with destruction and guilt–an emotion consuming the Monster. Understanding the impetus of his own despair and isolation is Victor’s wish to create a race to worship him, the Monster assumes the role to reciprocate the same desolation to Victor. In this way, the Monster and Victor invent and inhabit a twisted symbiotic relationship of their own, self-obsessed creation.

Shelley contrasts dire scenes of isolation with the glory of temporary, restful solitude to ultimately highlight the importance of community and show that mankind cannot live without others. In the Monster’s wish to belong within mankind’s social systems, Shelley underscores the importance of human companionship and communion with others. Rejected from everyone around him, the Monster longs to have a meaningful connection with someone, anyone. The Monster in “the reflections of my hours of despondency and solitude” watches the beauty of human connections all around him (Shelley 95). The “despondent solitude” that the Monster refers to is his isolation and utter social outsidedness. His disposition brings him emotion beyond sadness but one of total “despondency” (a feeling connected to a lack of total joy) and anguish. And although in this scene the Monster has not yet reached his height of danger, he still is suffering from the ramifications of his lonely torment. In his reflections on community of the De Lacey he finds “their amiable and benevolent dispositions” and he longs for a companionship with this goodness: “I persuaded myself that when they should become acquainted with my admiration of their virtues, they would compassionate me, and overlook my personal deformity” (Shelley 95). In this hopeful section, the Monster recognizes that although his differences cannot be changed, he remains hopeful because of the goodness (“virtues,” “compassionate”) he perceives in the De Laceys. He believes they will “overlook” his “personal deformity” and welcome him into fellowship / community with them. In this way, the Monster seems to suggest that communities understand and recognize faults but still band together in communion. This is exactly what the Monster longs for. In this scene, the Monster tells Victor in his naivety that he persuaded himself into believing that he could belong in a community that would “overlook” his faults. The passage shows the childlike simplicity of Monster’s values. Like a child, the Monster hopes to belong within society and holds a very human wish for belonging. However, after repeated rejection, the Monster, now an “adult” who understands his isolation from humans, gives up on his dream to be involved in mankind’s sociality and turns toward a new type of community.

As the Monster’s dreams of joining human society die, the creature decides that it is the creator’s responsibility to give their creation community–and thus he turns to Victor to help relieve his “despondency.” The Monster has studied Paradise Lost and the Biblical narrative where God created man and woman–he knows Adam and Eve were created to have communion together. The Monster understandably wishes for an Eve, “I was alone. I remembered Adam’s supplication to his Creator; but where was mine?” (Shelley 96). In a simple statement, “I was alone”, directed at his creator–the only being with the ability to create a companion for him– serves to stir a feeling within Victor, evoking some sympathy for his plight. With no hope of ever belonging in human community, the Monster can only rely on his estranged creator to give him relationship with one of “his own kind.” The Biblical references act as a framework Shelley uses to exemplify the power dynamic of Victor and his Adam. Victor, God to the Monster, is tasked with fulfilling his duty as a creator; and the Monster, Adam to Victor, must in turn fulfill his duties toward Frankenstein. In the power dynamics framed by the Biblical allusions of this relationship, the Monster’s claim that companionship is a right as given by the creator is strengthened because the God in Paradise Lost gave his Adam, an Eve. Through the Biblical example, the dependent relationship of creator and created becomes increasingly clear. After the Monster’s pithy statement on his plight, he pleads as Adam “supplicates” for a companion: “Oh! my creator, make me happy; let me feel gratitude towards you for one benefit! Let me see that I excite the sympathy of some existing thing; do not deny me my request!” (Shelley 107). The Monster, although he believes it to be his right for Victor to create him a female, still pleads and begs Frankenstein with emotion using phrases like “oh!” “excite sympathy,” and “do not deny me my request!” Although the creature compares Victor to God, he still understands Victor, a human, is not the same kind of creator he read about in Paradise Lost and thus he begs and pleads with him for mercy and justice. The emotional apex emotion comes as the creature expresses his credence that companionship is a right and thus vital for any creation. This core principle outlines the beginnings of Shelley’s emphasis on the unbreakable connection between meaningful communion and a meaningful life.

This quest for relationship is not only pushed forward by the God-Adam dynamic but also the father-son dynamic that Victor and the creature inhabit. Laura Claridge in her criticism of Frankenstein, “Parent-Child Tensions in Frankenstein: The Search for Communion” depicts the relationship between Victor and the Monster as a father and son arguing that this parent-child relationship most closely mirrors the creator-created relationship depicted in Frankenstein. Claridge writes, “It is not, then, the Monster’s nature that makes him so vengeful, as his creator deludes himself into thinking, but rather his overwhelming sense of isolation and despair at lacking human connections that in fact his father should have first provided” (Claridge 7). Claridge, rightfully illustrates the “Monster’s vengeful nature,” however, she is clear that it is not in fact the Monster’s innately positive nature’s fault, but rather the lack of responsibility Victor (the Monster’s “father”) has on giving the Monster community. Although the Monster begins to understand the importance and vitality that community gives to humanity and the created, his belief and Victor’s belief on the matter diverge and thus cause major conflict between the pair. Additionally, Claridge points out the difference in attitude of the Monster and Victor to isolation and community themselves: “Of major significance in the struggle between Frankenstein and his monster are the efforts of the creator to escape his place in society, in contrast to the desperate attempts of the created to become situated within it” (Claridge 8). The Monster clearly longs for community–first wanting to be a part of humanity, later settling to be an Adam provided with an Eve. By contrast, Victor longs to leave society, he largely abandons his loved ones, stating clearly that “I abhorred society” (Shelley 120). The Monster, believing it is his right either by Victor’s nature of being his “God” or by his nature of being his “father”, is indignant upon not receiving his own community. Victor, hardened, isolated, and wanting to be separate from society, does not fulfill his “godly” or “fatherly” duty and kills the Monster’s only chance at any real communion. This tension ultimately leads to a final back and forth showdown between the two protagonists.

Ultimately, because Victor doesn’t give the Monster his Eve, the Monster continues his murderous attacks on Victor’s community. These murders ultimately and fully isolate Victor. Victor, after flirting with creating a companion of the Monster, ends the scene with the “aborted Eve.” The Monster watches through the window as Victor destroys his only possible companion. After not living up to the Monster’s ideals of what creator ought to be, he terrorizes Victor. He retaliates, killing Clerval, and taunts Victor by threatening to kill Elizabeth saying, “I will be with you on your wedding night” (Shelley 127). The Monster is cognizant of Victor’s life events, including his relationship with Elizabeth, illustrating how intertwined their lives have truly become. Rather than directly targeting and killing Victor, the Monster threatens his friends, family, and community–the very things Victor has not provided for him. This repeated process of murdering those around Victor also forcibly pulls Victor deeper into the same type of isolation the Monster faces. Victor loses all his connections and his loved ones, but also is emotionally wrecked with his guilt and responsibility for these deaths. In a similar reaction to William and Justine’s deaths (these deaths Victor is also responsible for by creating the creature), Victor is also faced with the reality of his complicity in the deaths of his other family members. Forced into his own overwhelming isolation, Victor also becomes consumed with revenge, mirroring some of the emotions and actions of the Monster. The Monster and Victor have now created their own type of hateful companionship, driven by the dangerous isolation they forced on each other.

The new, destructive symbiotic relationship formed between Victor and the Monster illustrates Shelley’s argument that community and relationship gives life meaningful purpose. The Monster and Victor following the deaths of Elizabeth and Victor’s father begin a journey of mutual hatred and revenge. They chase after each other, Victor says, “I pursued him; and for many months this had been my task” (Shelley 152). Victor calling his vengeance on this creation being “his task of many months” shows how this relationship has consumed Victor for a long period of time–and thus this gives his life meaning and purpose. The creator-created pair form an interesting companionship that gives life a purpose and drive which neither of the characters were able to fulfill with any other person in the novel prior. The Monster, desolate and alone, could not find companionship with any living creature.However by the end of the novel, he has created a strange, albeit dysfunctional companionship with his creator. Victor, in a similar way, was not driven in the same way by any other character in the novel. Not even his closest companion, Elizabeth, could give his life meaning like the Monster does at the end of the novel. Although a deeply twisted purpose of mutual death, the perverted dependency revives both Victor and the Monsters’ meaning in life–so they “pursue each other for months.” The Monster in passion for his purpose leads Victor across the globe, “Sometimes he himself, who feared that if I lost all trace I should despair and die, often left some mark to guide me…‘My reign is not yet over,’ (these words were legible in one of these inscriptions); ‘you live, and my power is complete. Follow me… eat and be refreshed’” (Shelley 152- 154). The Monster actively tries to protect the life of his enemy only to further keep his companionship with him using words like “despair” and “death.” Together this new manifestation of community gives both of their lives a meaningful, purposeful life.

Through creating a deep connection that gives both characters a purpose in life, Shelley ultimately reveals how purpose cannot be derived in solitary isolation, but requires others to contribute to it. Colene Bentley in“Family, Humanity, Polity: Theorizing the Basis and Boundaries of Political Community in Frankenstein” writes the relationship between Victor and the Monster, despite the physical distance, reveals the enduring meaning of connection. She writes, “That Shelley’s characters shadow each other for the remainder of the novel demonstrates the need to be cognizant of (absent) others to whom one is nonetheless politically bound” (Bentley 17). Bentley uses the term “politically” to mean socially related or a part of a shared community. She continues, “one cannot conveniently excise others for one’s moral purview, as Victor tries to do and the creature persistently reminds him that he cannot” (Bentley 17). Bentley makes the argument that throughout the novel, Victor attempts to create distance between himself and his creation. This factors into why Victor agrees to create a companion for the Monster because the Monster says he will flee Europe and not bother Victor again. However, as Bentley acknowledges, the ties created by the Monster and Victor cannot be broken nor forgotten about. Although physically a member of a communion may be “absent,” others in the communion must be aware and “cognizant” of each other. This is what Frankenstein and the Monster embody at the end of the novel: A haunting, permanent connection that gives life a (horrifying) sense of purpose.

Lastly, the death of Victor and the subsequent reaction of the Monster shows how community and the purpose derived therein is what drives life itself. After Victor’s storytime and impassioned speech to the sailors on not turning back, Walton finds Victor dead, “I entered the cabin, where lay the remains of my ill-fated and admirable friend,” but he also finds Victor’s creation hanging over him, “Over him hung a form which I cannot find words to describe; gigantic in stature” (Shelley 164). The Monster immediately comes to Victor after his passing–the one community the Monster had experienced (however dysfunctional) was broken by the death of his creator. Even the image of the creature “hanging” over the body illustrates a closeness between the pair. Like a child who hangs onto a parent, the creature “hangs” over the body of the dead creator, Victor. The Monster even exclaims that he murdered Victor by destroying all of his former community, “I, who irretrievably destroyed thee by destroying all thou lovedst” (Shelly 164-165). The Monster seems to have some remorse for what he has done to Victor, tormenting him, killing his loved ones. He seems to understand the gravity of the situation, of losing the only being with whom he experiences any type of communion. This obsessive nature of both “father” and “son” ends in both of their ultimate deaths. As the Monster hangs over Victor’s body talking to Walton, he expresses his own desire to die. The Monster says, “I shall collect my funeral pile, and consume to ashes this miserable frame…I shall die. I shall no longer feel the agonies which now consume me…He is dead who called me into being; and when I shall be no more, the very remembrance of us both will speedily vanish” (Shelley 167). Following the death of his creator, the Monster decides to complete Victor’s wish to destroy what he has created. The Monster even uses the word “both” to show the communion between the pair–together both of their “remembrances” will be forgotten. In the end, the relationship between the two protagonists gradually formalizes and comes to light, giving both parties a purpose and meaning. In the end, however, together they will “both” be forgotten and pass away as they are the only true community either truly experienced.

Throughout Frankenstein, Shelley demonstrates the fragile, yet essential role community plays in a purpose-filled human life. Victor eschews community, leading to his downfall; the Monster envies community, leading to his murderous rage. Shelley’s careful portrayal of this symbiotic relationship depicts her emphasis on others to elevate life’s purpose to something bigger than oneself. Even the connection Victor and the Monster build upon mutual destruction gives both characters’ lives a deeper meaning. By contrast, Shelley shows how isolation from society–either by force or self imposed–ends in horrible destruction and the creation of monsters. Shelley celebrates the redemptive power of solitude, but warns of the dangers of prolonged isolation. Like a true Romantic, Shelley weaves in moments of beautiful nature spent peacefully alone, but never neglects to point back to human’s ultimate need for community and companionship. Frankenstein illuminates the truth that community is essential to our existence and our purpose as created beings. The book is a stark warning against self-obsession–playing God and demanding our way–which poisons community and leads to life-destroying isolation.

READ MORE:

Leave a comment